| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

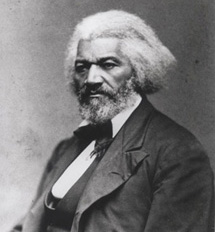

IntroductionSlavery existed in the United States since colonial days. By the middle of the 19th century, it had been outlawed in the North, but continued to exist in the South, where it formed a central part of the agricultural plantation economy. Africans were captured and brought to America to work in the fields, held in bondage by laws and violence. Many slaves resisted and although it was difficult, escaped to freedom. The Underground Railroad helped thousands of slaves escape, and slave rebellions threatened what was called the “peculiar institution.” The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 sought to uphold slavery by pledging federal government assistance to owners seeking runaway slaves. Meanwhile, the abolitionist movement grew in the years before the Civil War, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book Uncle Tom’s Cabin portrayed the horrors of slavery and converted millions of people to the anti-slavery cause. The election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860 increased the tension. Although Lincoln did not promise to abolish slavery, but rather to keep slavery from expanding to the Western territories and new states, the Southern states feared for their independence and way of life. The Confederate States of America formed when South Carolina seceded in 1860, and the following year Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina joined the Confederacy. The war started after the Confederates fired on federal troops at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina in April 1861, and Lincoln called for a volunteer army to defend the Union. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 freed the slaves in the states in rebellion against the US, but not in areas under Union control (the border states of Maryland, Delaware, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri, and parts of Tennessee, Louisiana, and Virginia). African-Americans left the plantations and headed north, and some joined the Union army to fight against the South. Although slavery had been abolished, racial prejudice continued to exist in the North and South, and separate “colored” units were formed. After the war, the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ended slavery in America. Former slaves worked to improve the lives of African-Americans and struggled against continuing discrimination, relying on the strength of their families, religious institutions, traditions, and communities. Not until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s did African-Americans achieve a significant degree of social equality. This section includes handwritten documents about the sale of slaves, an advertisement for reward money for fugitive slaves, abolitionist newspapers, drawings of slave girls freed at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, and President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation issued January 1, 1863. Photographs include slave life in the South, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass (two African-Americans who were influential during and after the Civil War), and African-American soldiers. Also included are photographs of artwork commemorating Harriet Tubman’s bravery in leading 300 slaves to freedom. DocumentsSelect images from the list below and click on the link to read more. Each image can be enlarged to view more details. To browse through the images, start at the first image and follow the “slavery” link for more on this theme. About the Project | Feedback | Brooklyn Collection | Brooklyn Daily Eagle Online |

||||||||||||||